Chinese Gardens

The classical Chinese garden is enclosed by a wall and has one or more ponds, a rock garden, trees and flowers, and an assortment of halls and pavilions within the garden, connected by winding paths and zig-zag galleries. By moving from structure to structure, visitors can view a series of carefully composed scenes, unrolling like a scroll of landscape paintings. Flowers and trees, along with water, rocks and architecture, are the fourth essential element of the Chinese garden. They represent nature in its most vivid form, and contrast with the straight lines of the architecture and the permanence, sharp edges and immobility of the rocks. They change continually with the seasons, and provide both sounds (the sound of rain on banana leaves or the wind in the bamboo) and aromas to please the visitor. Each flower and tree in the garden had its own symbolic meaning. The pine, bamboo and Chinese plum were considered the "Three Friends of Winter”. The pine was the emblem of longevity and tenacity, as well as constance in friendship. The bamboo, a hollow straw, represented a wise man, modest and seeking knowledge, and was also noted for being flexible in a storm without breaking. Plum trees were revered as the symbol of rebirth after the winter and the arrival of spring. During the Song Dynasty, the favourite tree was the winter plum tree, appreciated for its early pink and white blossoms and sweet aroma. The peach tree in the Chinese garden symbolized longevity and immortality. Peaches were associated with the classic story The Orchard of Xi Wangmu, the Queen Mother of the West. This story said that in Xi Wangmu's legendary orchard, peach trees flowered only after three thousand years, did not produce fruit for another three thousand years, and did not ripen for another three thousand years. Those who ate these peaches became immortal. This legendary orchard was pictured in many Chinese paintings, and inspired many garden scenes. Pear trees were the symbol of justice and wisdom. The word 'pear' was also a homophone for 'quit' or separate,' and it was considered bad luck to cut a pear, for it would lead to the breakup of a friendship or romance. The pear tree could also symbolize a long friendship or romance, since the tree lived a long time. The apricot tree symbolized the way of the government official. The fruit of the pomegranate tree was offered to young couples so they would have male children and numerous descendants. The willow tree represented the friendship and the pleasures of life. Guests were offered willow branches as a symbol of friendship.

An ancient Chinese legend played an important part in early garden design. In the 4th Century B.C. a tale in the Shan Hai Jing, or Classic of Mountains and Seas, described a peak called Mount Penglai located on one of three islands at the eastern end of the Bohai Sea, between Japan and Korea, which was the home of the Eight Immortals. On this island were palaces of gold and platinum, with jewels on the trees. There was no pain, no winter, wine glasses and rice bowls were always full, and fruits, when eaten, granted eternal life. In 221 B.C. Ying Zhen, the King of Qin, conquered his rivals and unified China into an empire, which he ruled until 210 B.C.. He heard the legend of the islands and sent emissaries to find the islands and bring back the elixir of immortal life, without success. At his palace near his capital, Xianyang, he created a garden with a large lake called the Lake of the Orchids. On an island in the lake he created a replica of Mount Penglai, symbolizing his search for paradise. After his death,his capital city and garden were completely destroyed, but the legend continued to inspire Chinese gardens. Many gardens have a group of islands or a single island with an artificial mountain representing the island of the Eight immortals.

Chinese influence on the Japanese garden The Chinese classical garden had a notable influence on the early Japanese garden. The influence of China first reached Japan through Korea before 600 CE. In 607 AD the Japanese crown prince Shotoku sent a diplomatic mission to the Chinese court, which began a cultural exchange lasting for centuries. The Japanese Ambassador to China, Ono no Imoko, described the great landscape gardens of the Chinese Emperor to the Japanese court. His reports had a profound influence on the development of Japanese landscape design. During the Nara period (710-794), when the Japanese capital was located at Nara, and later at Heian, the Japanese Court created large landscape gardens with lakes and pavilions on the Chinese model for aristicrats to promenade and to drift leisurely in small boats, and more intimate gardens for contemplation and religious meditation.[72] A Japanese monk named Eisai (1141–1215) imported the Rinzai school of Zen Buddhism from China to Japan, which led to the creation of a famous and unique Japanese gardening style, the Zen garden. He also brought green tea from China to Japan, originally to keep monks awake during long meditation, giving the basis for the tea ceremony, which became an important ritual in Japanese gardens. The Japanese garden designer Muso Soseki (1275–1351) created the celebrated Moss Garden in Kyoto, which included a recreation of the Isles of Eight Immortals, called Horai in Japanese, which were an important feature of many Chinese gardens. During the Kamakura period (1185–1333), and particularly during the Muromachi period (1336–1573) the Japanese garden became more austere than the Chinese garden, following its own aesthetic principles.

Chinese gardens in England and Europe

The novelty and exoticism of Chinese art and architecture in Europe led in 1738 to the construction of the first Chinese house in an English garden, at Stowe House, alongside Roman temples, Gothic ruins and other architectural styles. The style became even more popular thanks to William Chambers (1723–1796), who lived in China from 1745 to 1747, and wrote a book, The Drawings, buildings, furniture, habits, machines and untensils of the Chinese, published in 1757. He urged western garden designers to use Chinese stylistic conventions such as concealment, asymmetry, and naturalism. Later, in 1772, Chambers published his Dissertation on Oriental Gardening, a rather fanciful elaboration of contemporary ideas about the naturalistic style of gardening in China.

Chambers was a fierce critic of Capability Brown, the leading designer of the English landscape garden, which Chambers considered boring. In 1761 he built a Chinese pagoda, house and garden in Kew Gardens, London, along with a mosque, a temple of the sun, a ruined arch, and Palladian bridge. Thanks to Chambers Chinese structures began to appear in other English gardens elsewhere on the continent. Many continental critics disliked the term English Garden, so they began to use the term 'Anglo-Chinois" to describe the style. By the end of the nineteenth century parks all over Europe had picturesque Chinese pagodas, pavilions or bridges, but there were few gardens that expressed the more subtle and profound aesthetics of the real Chinese garden.

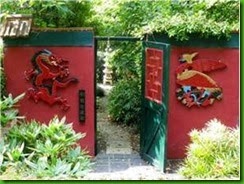

Chambers was a fierce critic of Capability Brown, the leading designer of the English landscape garden, which Chambers considered boring. In 1761 he built a Chinese pagoda, house and garden in Kew Gardens, London, along with a mosque, a temple of the sun, a ruined arch, and Palladian bridge. Thanks to Chambers Chinese structures began to appear in other English gardens elsewhere on the continent. Many continental critics disliked the term English Garden, so they began to use the term 'Anglo-Chinois" to describe the style. By the end of the nineteenth century parks all over Europe had picturesque Chinese pagodas, pavilions or bridges, but there were few gardens that expressed the more subtle and profound aesthetics of the real Chinese garden. Beggars Knoll Chinese Garden: Newtown, Westbury, Wiltshire. This inspirational 1-acre garden is filled with colourful plantings set against a backdrop of Chinese pavilions, gateways, statues and dragons. Pathways and mosaic pavements wind around ponds and rocks. Rare Chinese shrubs, mature trees, and flower-filled borders form a haven of serenity.

A large potager houses chickens, and pigs live in the woods. The garden is set on a steep chalk hillside with a beechwood as backdrop. It is divided up into a series of Chinese 'rooms' separated by walls, hedges and gateways. There are collections of Chinese viburnums and of podocarps, and there is a bamboo garden with its own pavilion.

A large potager houses chickens, and pigs live in the woods. The garden is set on a steep chalk hillside with a beechwood as backdrop. It is divided up into a series of Chinese 'rooms' separated by walls, hedges and gateways. There are collections of Chinese viburnums and of podocarps, and there is a bamboo garden with its own pavilion.

No comments:

Post a Comment